#51 - Flashes of Brilliance

Anika Burgess on her new book and the experimental spirit of early photography

About halfway through Flashes of Brilliance, Anika Burgess offers a quietly barbed moment of historical irony. “Photography is truth embodied,” an anonymous commentator declared in 1867—a statement that, as Burgess makes clear, was as inaccurate then as it is now.

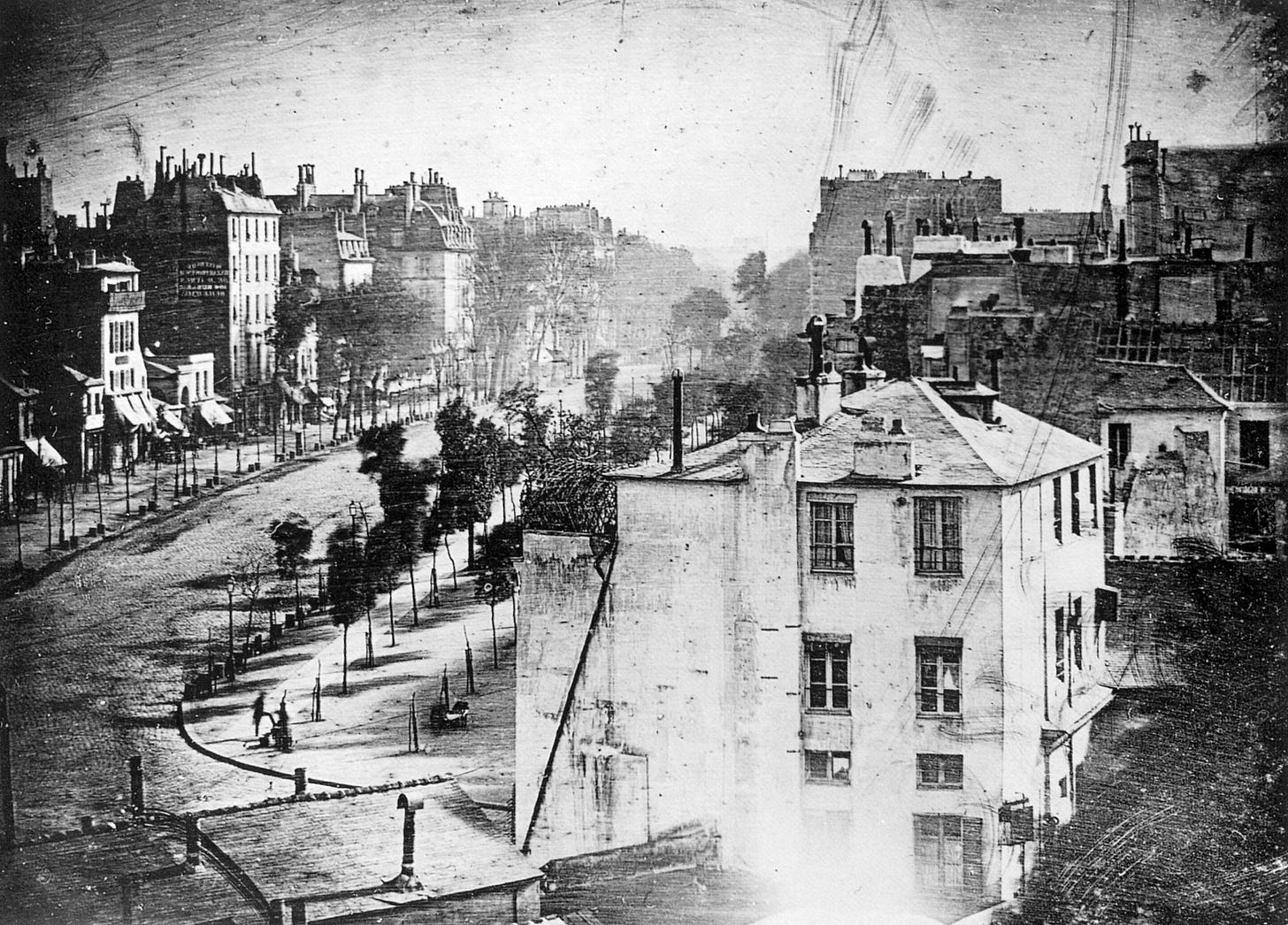

Burgess elaborates: from its earliest exposures, photography revealed a selective relationship to reality. Take Daguerre’s 1838 image of the Boulevard du Temple, often cited as the first photograph to depict a human figure. The Parisian street appears uncannily deserted—not because it was empty, but because the long exposure time erased anything in motion. The only figure that remains is a man having his shoes shined, visible simply because he stood still long enough to register on the plate.

Early photographers quickly discovered their medium's technical boundaries. Lenses warped perspective, chemical processes could only render scenes in black and white, and long exposures meant that anything in motion simply vanished from the frame.

As Burgess details, photographers did not treat these technical constraints as problems to be solved. Instead, they embraced them as creative possibilities. They retouched prints by hand, stitched together multiple negatives, and by the late 1870s, were purchasing stock photographs of clouds to lend their skies a touch of drama. Vendors marketed these visual enhancements with striking candor; one ad promised, simply and enthusiastically, “No More Inartistic Monotonous Background to Landscapes, Views, &c.”

A joltingly candid embrace of fakery—especially striking today, when anxieties about manipulation, forgery, and photographic “truth” are again front and center in the age of AI.

Moreover, Burgess suggests that anxieties about photographic manipulation are not uniquely modern—they trace back to the very birth of the medium. The photograph, she argues, has always occupied a slippery space between record and artifice.

Flashes of Brilliance is less a linear history than a guided tour through photography’s early experiments and ambitions. Burgess deftly moves across decades and disciplines: from X-rays to cave photography, balloon crashes to suffragist surveillance. Throughout, she remains attuned to the ingenuity—and, often, the physical risk—required of these early image-makers.

Informed by her work at Atlas Obscura and her archival editing on The New York Times’ Past Tense project, Burgess draws from a deep well of visual history and research obsession. While she doesn’t claim a direct line between these nineteenth-century innovations and today’s digital tools, her book deepens our appreciation for the long arc of photographic experimentation and invention.

Flashes of Brilliance is available for preorder now from W. W. Norton and is on shelves July 8.

Recently, I corresponded with Anika about her path into the history of photography, her approach to structuring Flashes of Brilliance, and what today’s image-makers might learn from photography’s risk-taking pioneers.

Can you tell me about your background and how you came to specialize in photo editing and photography history?

I graduated from university with degrees in arts (history and performance) and law. But after a few years working in legal and compliance in London, I realized I needed to work in a more creative field. Having always been interested in photography, I took a course in photo research which was taught by a photo editor at Penguin Books. She then hired me to work on photography and clearances for the Penguin Modern Classics redesign. It was such a thrill to work on archival photography and artwork for these iconic titles — truly it was the best possible introduction to publishing and archival research.

After that I freelanced as a photo editor, which included assigning shoots, but kept up my interest in photo history and photo archives and wherever possible, I incorporated that into my work. That continued when I moved to New York, and at Atlas Obscura, where I started writing about archival photography, and when I came to work at The New York Times as a freelance photo editor on the archival storytelling initiative Past Tense.

What inspired you to write Flashes of Brilliance? Was there a particular photograph or photographer that first sparked your fascination?

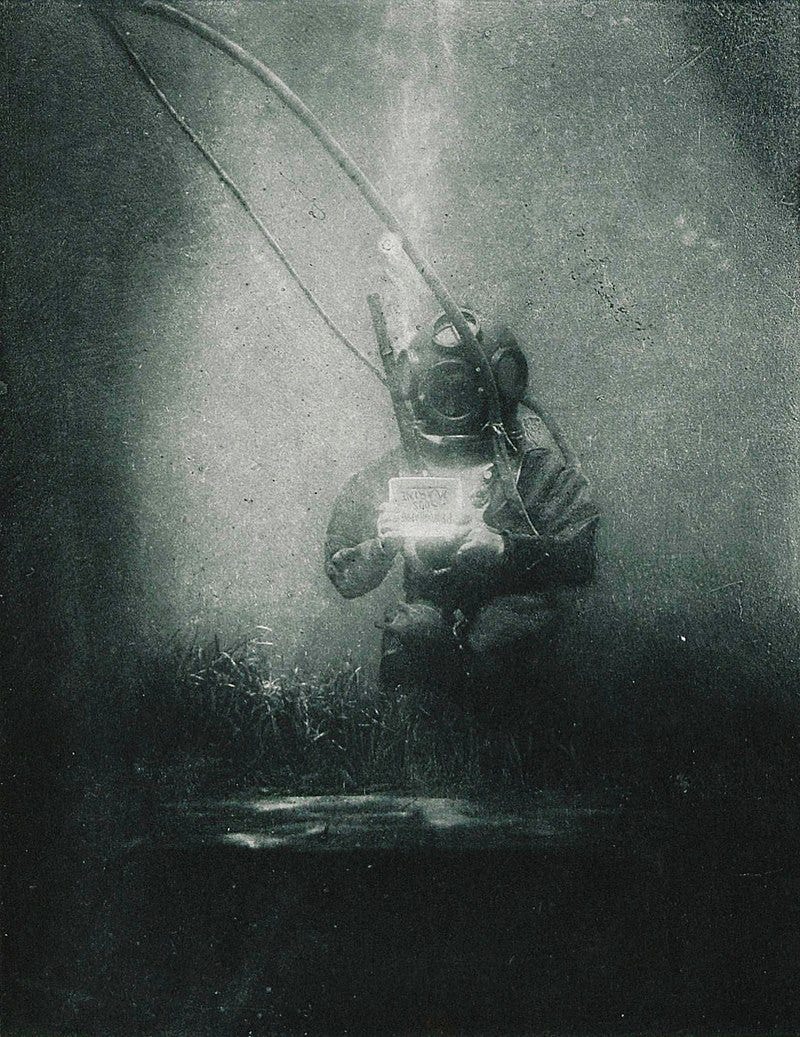

Yes — one day I stumbled across an underwater photo of a diver. He was pictured in one of those old diving suits with a helmet, holding a sign, and the website said it was from the 1890s. I did more research and learned that it was taken by a French marine biologist named Louis Boutan. For that photo, Boutan had pulled the shutter from a boat above, using a cord attached to the underwater camera. The diver’s sign reads “Photography Sous Marine”, but rather delightfully, if you look closely, you’ll see that it’s upside-down.

I was so struck by this as an experiment, and as a photograph, that I researched the whole history of underwater photography, which, remarkably, goes all the way back to the 1850s. What was so fascinating to me, and so surprising, was the openness to experiment, and the sheer optimism required to attempt underwater photography in the 1850s. And that was the jumping off point to research how early photography was far more innovative and experimental and, at times, dangerous, than it may first appear.

How did your work editing The New York Times' Past Tense initiative influence your approach to Flashes of Brilliance?

As any freelancer knows, some jobs are more inspiring than others, but Past Tense was an utterly unique and special opportunity. It’s an extraordinary archive and photo heritage. It didn’t influence my approach to the book, but it did feed my fascination with archives.

Which experimental techniques that you discovered surprised you most? Were any particularly dangerous for the photographers?

So many; in some ways it’s a wonder anyone survived early photography. I knew that photographers had experimented with taking photos using a kite and an automatic shutter. What I didn’t know was that a few also tried to do it while attached to the kite themselves. One aviation enthusiast and amateur photographer suspended himself from a kite at a height of some 300–400 feet to take photos.

I was also surprised to learn that, in the early days of X-ray images, photo equipment manufacturers sold X-ray equipment which they advertised alongside their cameras in photo journals. Of course, because X-rays were not yet fully understood, no one really took any precautions in regard to radiation exposure.

How did you decide which photographers and experiments to include? Were there stories you were reluctant to cut?

I structured the book around three topic areas. Briefly, the first relates to the physical world, such as photographing the moon and underground; the second relates to format, such as mammoth photography and photo manipulation; and the third centers around the role of photography in science, including X-rays and motion. Any one of these topic areas could be an entire book so I did have to kill some darlings. Specifically, I loved reading about retinal photography, which was based on the nineteenth-century belief that when you died, the last thing you saw stayed imprinted on your retina and could be photographed. As you can imagine, this would have huge implications for murder cases, if only it were true. I was sorry to lose that section.

What challenges did you face researching and verifying these historical accounts?

One challenge early on was the logistics of researching during COVID, in terms of going to libraries. Fortunately, the NYPL library card provides access to a lot of online nineteenth-century photo journals and reading those became something of an obsession. The challenge there was knowing when to stop.

Do you see parallels between early photography pioneers and today's photographic innovators?

I think one of the key aspects of photographic innovation, then and now, is the aspiration to stretch photography as a medium in new and unseen ways. But other than that, I’d prefer to not see too many parallels; many of the pioneers in my book had little sense of their own self-preservation or mortality.

What do you hope readers take away from Flashes of Brilliance? Any techniques that could inspire today’s photographers?

So much! Today it is so simple to take a photograph; I hope that, by knowing some of the wild experiments and surprising stories from photography’s early decades, they will have a deeper recognition of how taking a photograph is a kind of magic. I hope readers are surprised by some of the innovations, and at how seemingly contemporary photo debates — for example, over surveillance or manipulation — began in the nineteenth century. And I hope they’re entertained by the stories and the photographs. I wanted to write a photo book that people could take on the subway and read, rather than keep on a coffee table. I wanted it to be accessible, in the same way that photography is today.

Do you enjoy looking at photo books in your spare time? Any that you particularly enjoy or find yourself returning to?

I do, and I have quite a few. As you can imagine, most are on photo history or feature archival photographs. One chapter in my book is about “psychic photography”, the idea that you can photograph thoughts and dreams, and there’s some wonderful images in the book Photography and the Occult. I’m fascinated by the early years of photojournalism in the 1930s and so I have several books by Dorothea Lange and Margaret Bourke-White. For contemporary work, last year I bought Mikko Takkunen’s Hong Kong. Having lived there as a child, I loved returning to the city through Mikko’s gorgeous photographs.

Has researching early photography's experimental spirit changed how you approach your current photo editing work?

While I researched and wrote this book, I freelanced as a photo editor and found it a strange juxtaposition to go from reading about nineteenth-century photography, which could be so painstaking, to the world of twenty-first-century photography, with its innumerable, instant digital frames. But to paraphrase one of the book’s epilogues: photo progress has come from all the experiments and failures of those who came before. The time I have spent on my book has deepened my appreciation and admiration for the work that photographers do, and for photography itself.

To explore more of Anika’s writing and archival photo finds, please visit her website or follow her on Instagram.

Cool! I got sent the book last week and am enjoying it so far.

What an interesting book! Will be adding it to my reading list