From the first through third grade, I attended St. Thomas More Cathedral School in Arlington, VA—a wholly unremarkable fact except that I was the only non-Catholic child in my class and thus excluded from most Catholic activities. While the rest of the class took communion at Friday mass, I was banished to the farthest pew to stew in my parents' poor Protestant decisions. This arrangement persisted for several months until the principal, Sister Carmel Regina, caught me red-handed with my makeshift sacrament: contraband Dunkaroos and Hi-C Ecto Cooler, along with a pilfered, dog-eared copy of a Boxcar Children book neatly hidden inside the Bible.

Now deemed wholly untrustworthy to sit alone, I had to be relegated to some duty befitting a non-Catholic that didn't require baptism. And so I was sentenced to pay penance by reading the first liturgy each Friday—an eye for an eye, a book for a book. The intended punishment was meant to terrify me—after all, how could I bear the horror of reciting Ecclesiastical Latin or reading scripture to a cathedral full of my Catholic peers when I myself hadn't passed the holy rite of catechism?

Yet the plan backfired spectacularly: I discovered an early love of public speaking and, for the next three years, dutifully (if not dramatically) read from the pulpit weekly.

I lost my faith out of embarrassment some years later when, shortly after moving to Western Maryland, I was jolted awake by a most vicious howling—like the blaring of some great trumpet. Fearing The Rapture™, I dropped to my knees in a last-ditch attempt to accept Jesus into my heart, only to discover salvation came through town twice nightly on the CSX rail line.

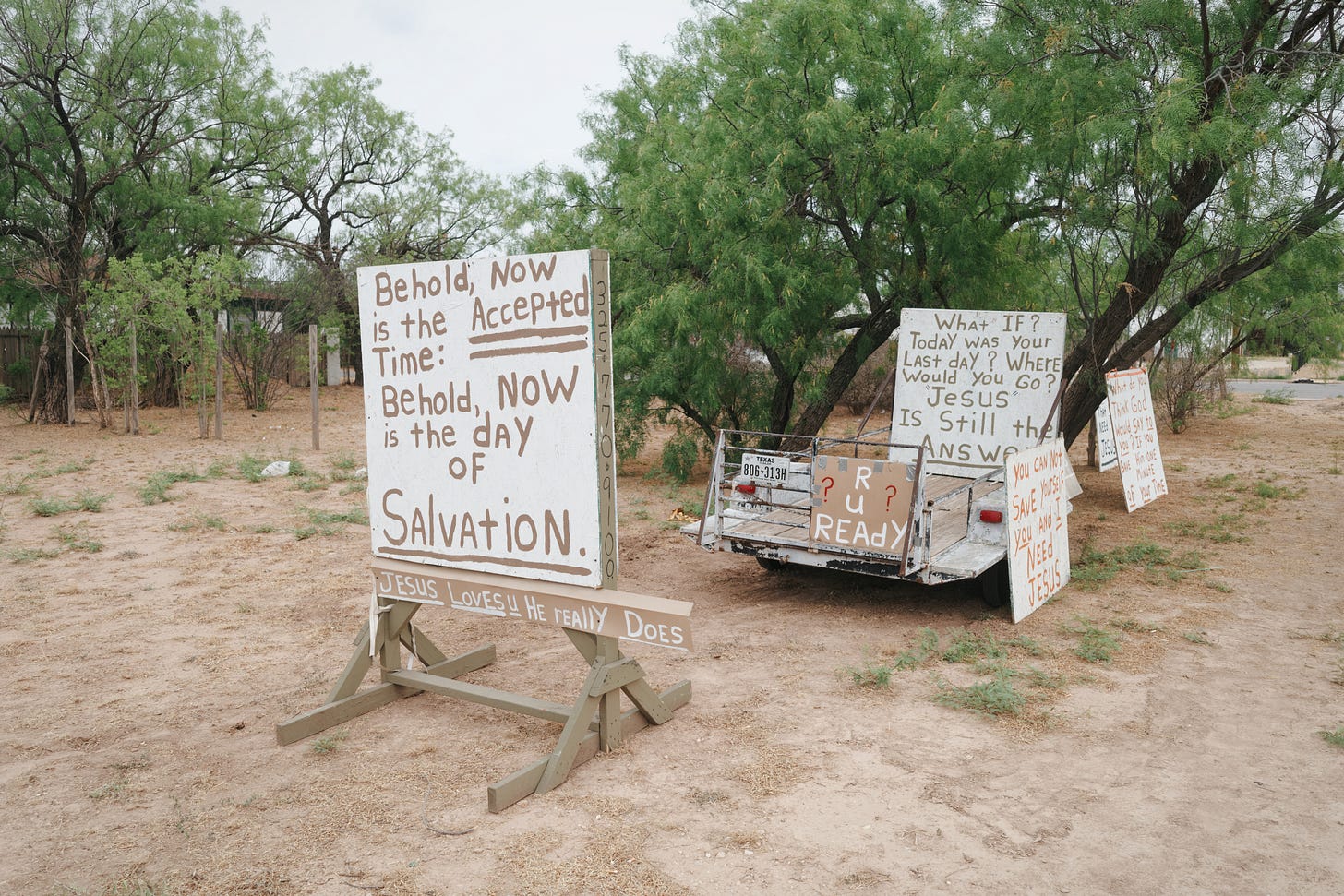

It would be years before I reëncountered divine messaging, though this time, it came not through the sonorous tones of a Catholic mass or the whistle of a misidentified Armageddon but via hand-painted signs hammered into the shoulders of Southern highways.

These makeshift evangelists—plywood rectangles adorned with amateur lettering and professional certainty about the fate of my eternal soul—dot the American South like modern-day burning bushes, though considerably less subtle.

A quick Biblical history lesson: Saul, a first-century zealot, made a name for himself hunting down early Christians, convinced he was doing God’s work. Then, on the road to Damascus, everything changed. A blinding light knocked him to the ground—off his high horse, literally—and he heard the voice of Jesus ask: "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?"

Struck blind, he was led into the city, where he spent three days in darkness until a Christian named Ananias laid hands on him, restoring his sight. Saul changed his Hebrew name to its Roman equivalent, Paul, and became the very thing he despised: a tireless evangelist, spreading the faith he once tried to destroy.

Unlike Saul on his journey to Damascus, I wasn’t struck blind by divine light. Instead, I found myself drawn to these roadside warnings, armed with a camera and a lingering appreciation for theatrical proclamations from elevated platforms.

Signs and wonders, the Bible calls them—miraculous markers meant to point the way. But where the faithful see proof, I see the hand-painted equivalents of Ozymandias’s pedestal: bold declarations of certainty, slowly crumbling under the weight of time and roadside neglect.

"FEAR GOD WHO HAS POWER TO SEND YOU TO HELL" loomed beside a road lined with abandoned houses. "GOD IS NOT MAD AT YOU NO MATTER WHAT" stood up the road from a swamp. "IS YOUR MOUTH FULL OF CURSING?" faced a movie theater in a cornfield.

What struck me most wasn’t their message—fire and brimstone is hardly original—but their persistence. These signs weren’t just warnings; they were conversion attempts, as subtle as a sledgehammer and as relentless as Sister Carmel Regina.

Like her, they seemed convinced that sheer repetition—whether through Ecclesiastical Latin or all-caps plywood proclamations—could save even the most hopeless heathen. But unlike Saul, who was struck blind by that divine light, most of us just drive past, barely noticing. The signs, once jarring, fade into the background, as commonplace as billboards for personal injury lawyers or ads for boiled peanuts. They become part of the scenery.

Perhaps, I am Paul become Saul: transformed from fearful believer to curious observer, and cataloging these roadside revelations not as divine truth, but as cultural oddities. Yet they fascinate me still—not for their answers, but for the questions they raise. Who makes these? How do you get one? And does anyone, speeding past in their car, ever actually see one, have an epiphany, and rush off posthaste to the nearest tabernacle to repent?

I love these signs because they’re less about miraculous conversion and more about our unshakable need to shout into the void, “HELL IS REAL!” while the void shouts back, “BUT DID YOU TRY THE BOILED PEANUTS?”

Thank you for your support, comments, and kind words week after week. If you enjoy what you read, consider sharing this newsletter with a friend who would enjoy it, too.

The intro music is "Mana Two - Part 1" by Kevin MacLeod

Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License

And as always, you can join me elsewhere on the web:

michaelwriston.com / Flickr / Glass / Bluesky

Photographer Matt Siber did a series about 15 years ago called “Floating Logos”. One of my favorite from the series was an image from Missouri of a billboard simply saying “Jesus” suspended in the air above a railroad crossing and a corrugated steel building. I was going to attach the image but don’t have the option on my iPad. Here’s a link to the series. The image is about half way down the page. https://www.siberart.com/floating-logos

I look out for signs like these when I'm out on road trips. They're a one of our top bits of Americana on our scavenger hunt list, to me just so interesting and sort of alien to me after being away from America for a decade and a half.